When South Korean workers began leaving the Kaesong Industrial Zone a couple of weeks ago, they returned across the border in cars and trucks laden with as much finished merchandise as possible.

Plastic-wrapped packages and boxes didn’t just fill the interior of cars but were stacked high on the roof, sometimes even covering the car’s bonnet and hanging off the back. After all, getting those goods to market was the prime concern at the time when people thought Kaesong operations might be suspended for a few days or weeks.

Now it’s looking like the shutdown will last longer and there are new concerns for South Korean companies that tie-up operations and pull out their remaining workers.

One of the most important issues they need to address is data security.

It was relatively easy to control access to offices when workers remained, but with everyone gone there’s no telling what will happen to the factories, facilities and their contents.

And that means that any data stored on computers in the offices, whether it’s company operational data, intellectual property or even private correspondence, could possibly be accessed if left behind.

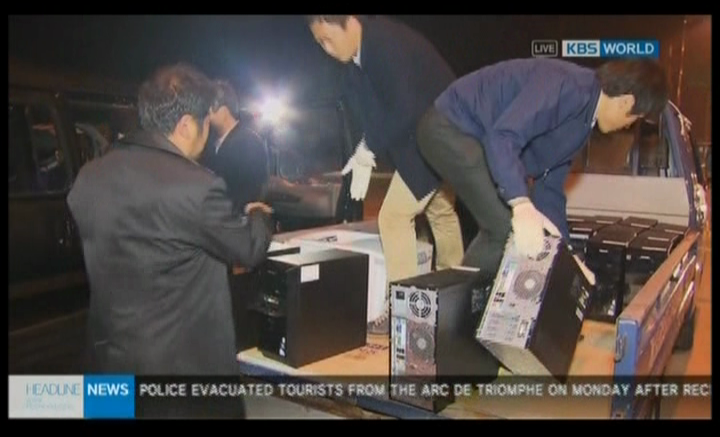

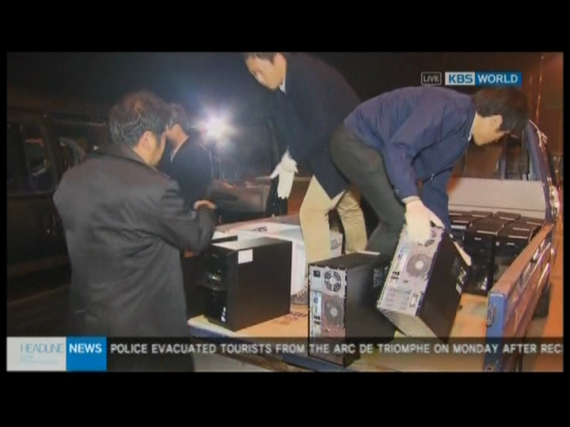

KBS broadcast images today of at least one truck that came across the border with desktop computers or servers that had been removed from offices.

And Woori Bank, the only South Korean bank inside the industrial zone, also brought back computers when it closed down operations on Monday. The bank handled wage payments to North Korean workers at the complex and contained transaction records for all South Korean companies in Kaesong, according to the Chosun Ilbo.

And Woori Bank, the only South Korean bank inside the industrial zone, also brought back computers when it closed down operations on Monday. The bank handled wage payments to North Korean workers at the complex and contained transaction records for all South Korean companies in Kaesong, according to the Chosun Ilbo.

They also brought back around US$100,000.

Bank staff had to be wary of North Korean wire taps when making phone calls with headquarters. “We refrained from discussing over the phone how much money was left in our safe,” a staffer said. — Chosun Ilbo, April 30, 2013.

Coincidentally, the Japanese Coast Guard is currently taking heat for poor data security measures. The Yomiuri Shimbun reported a decommissioned patrol vessel was sold by the Coast Guard to a scrap metal company without checking if the ship’s navigation computer had been wiped of tracking records.

The computer periodically records the position of the vessel and there’s worry by the Yomiuri that the data could reveal patrol patterns if accessed.

But why is this a big deal for the newspaper? Because the scrap metal company is owned by someone with membership of Chongryon, aka the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan — a pro-DPRK group.

The company owner assured the newspaper the boat and computer were both scrapped.