Tuesday’s series of denial of service attacks on major North Korean websites caused delays and frustration for legitimate users but doesn’t appear to have been as large or successful as the first round of attacks in late March and early April this year.

Analysis by NorthKoreaTech.org of data related to the attacks shows the so-called “OpNorthKorea” mission was most successful during its first few hours and then appeared to slowly tail off.

Denial of service attacks involve firing off requests for pages to websites. If enough requests can be sent, the site ends up overloaded and no one gets anything. Success of such an attack requires no hacking of the site itself, just enough people running attack software programs to overload the sites.

The remnants of the attack remain in slow load times for some sites, indicating some hackers are probably still trying targeting North Korean web servers but many have stopped.

Overall, the severity is much reduced from the last round, when global attention was focused on North Korean as it issued daily threats against South Korean and the United States.

The Attack Begins

There was some confusion over the precise starting time of the attack due to an error converting between local time and UTC/GMT.

#OpNorthKorea – 6/25 GMT 03 AM

12AM in Korean time.

03:00 UTC/GMT is actually 12pm local time, not midnight.

The targets of the attack were listed in an online file that was based on The North Korean Website List that resides on this site.

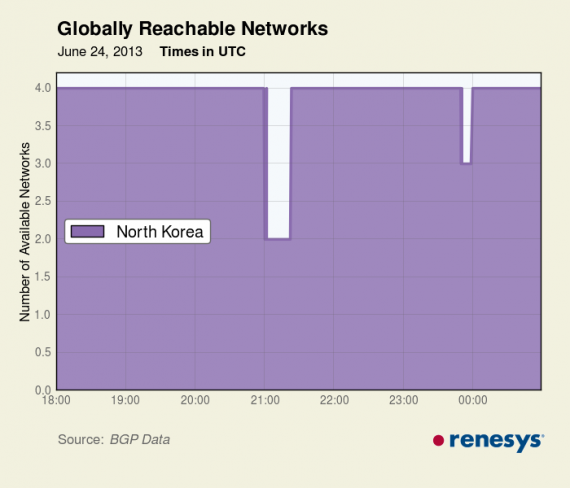

The start of the attacks appear to have triggered a couple of outage on the North Korean Internet, as can be seen in this graphic from Internet monitoring company Renesys. The first occurred at 3am local time and the second at just before 6am local time.

Data from Internet performance monitoring company Renesys shows an outage on the North Korean Internet just before midnight GMT on June 25.

The Targets

Korea Central News Agency (KCNA) and Rodong Sinmun in the DPRK, Choson Sinbo in Japan, the China-based Uriminzokkiri and the European-based Korea-DPR website of the Korea Friendship Assocation were among the main targets of the attacks.

But how successful were they?

Twitter began filling with “Tango Down” messages — signifying a website has been taken down — soon after the attacks began.

Were the sites really down, or just down for some users?

Frank Feinstein, who runs the KCNA Watch service, set up a page to track the success of attempts to connect to a host of North Korean related sites.

“While I don’t dispute the attacks have been successful, Anonymous have claimed many more sites to be ‘completely offline’ when they aren’t,” he said in comments to North Korea Tech. “I’m not sure how thorough they are with their checks but my data is often different from theirs.”

Feinstein runs several thousand proxy servers to repeatedly hit the KCNA website and grab the latest stories for his site. He used those to survey KCNA and a handful of other websites.

“Interestingly kcna.kp is not behaving very differently from the past weeks access logs. It seems to be standing up better than a lot of others,” he said. “From the selected North Korean sites I monitored, chosonsinbo.com was ‘down’ for a period of two hours, uriminzokkiri and ryugyongclip were also taken out.”

Uriminzokkiri was the target of a hack in April that resulted in details on the site’s 15,000 users being published on the Internet.

“kcna.kp was ‘totally unresponsive’ for less than 0.1 percent of the 24-hour period we have been monitoring it, which is within the margin of error,” he said. “Other sites have responded more strongly.”

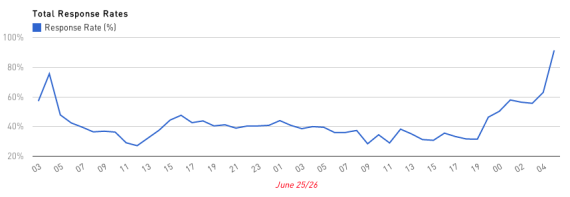

Feinstein’s data, shown below, indicates an average response rate of around 40 percent during much of the attack period. At some points it dipped below 10 percent for the sites being monitored.

A graph from KCNA Watch shows the response rate of North Korean websites over the period of a DDoS attack

For just the KCNA website, Feinstein’s monitoring showed a response rate of just 6 percent over the last 24 hours for his 1,214 attempts to grab content. If those numbers are representative of the average Internet user, that means many didn’t manage to connect to KCNA. To them, the site would have appeared down.

North Korea’s Internet Connection

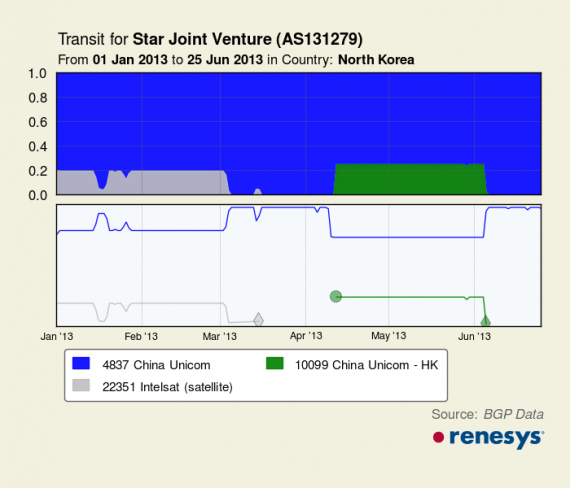

Ever since the DPRK first opened its connection to the Internet in 2010, the servers in Pyongyang have maintained their link with the rest of the world via China Unicom. About a year after it first connection, the DPRK added a backup route via satellite and things stayed the same until a couple of months ago.

Then, a third connection appeared via China Unicom Hong Kong. It appeared shortly after the April round of hacking attacks and the easy assumption was that it’s meant to help mitigate the attacks by providing another way for its servers to connect with users around the world.

Then, a couple of weeks before the long-planned June 25 attacks, it disappeared.

There’s no way of knowing why it appeared, just as there is no way of knowing why it was first added, but the original assumptions at least appear to be incorrect.

Here again is a graph from Renesys showing North Korea’s connection to the global Internet. The Intelsat connection (grey) disappeared around March this year. The China Unicom HK connection is shown in green.

“If those numbers are representative of the average Internet user, that means many didn’t manage to connect to KCNA. To them, the site would have appeared down.”

This is certainly true. I should add I have much more solid data on the kcna.kp site than others, as I’ve been doing this with kcna.kp for over a year. The KCNA actually site appears “down” in my location more often than not, and I don’t even bother to access it unless its through proxy servers (they are also getting really good at banning me). In this context, the site response rate to an average user would have been bad anyway, and once the attacks started there would have been no point trying to get your news from kcna.kp.

I’m so used to accessing anything North Korean through proxies, I sometimes forget that the average user wouldn’t think/be able to do it!